Melissa Amarello is one of the founders of Advocates for Snake Preservation, an organization committed to improving human tolerance of snakes and our peaceful coexistence with them. She studies their unique behaviors and mysterious social lives. In this interview, we discuss snake social behavior.

Q: Your research focuses on the social behaviors of snakes. Few people think of snakes as social, what drew you to study this little-known side of them?

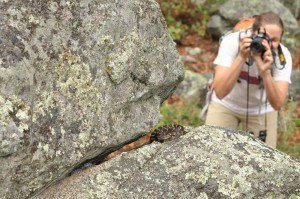

A: At the time we were pursuing an unrelated question for my graduate project. A friend showed my partner (Jeff Smith) and I a spot where we could increase our sample size, a communal den (where a group of animals spend the winter). When I shared details of our new study site with my graduate advisor, including how we observed snakes hanging out together, he strongly suggested we pursue this project instead.

Unlike many snakes that den in groups, this species, Arizona black rattlesnakes (Crotalus cerberus), doesn’t breed in the spring when they emerge. And den habitat is not limited, so they’re not forced to be together because they have nowhere else to go. So we wanted to know why and I think I recognized early the value of this type of project (both the subject and our methods of using remote cameras) for public education and changing how people view and treat snakes.

Q: In your work, you’ve found that some snake species actually spend quite a bit of time together. One of your current studies1 explores the idea that some members of rattlesnake families maintain close ties. Can you tell us more about that?

A: Despite observations dating back hundreds of years and peer-reviewed research published in the 1990s, most people believe that snakes are on their own, able to care for themselves, from the moment they’re born or the egg is laid. But many snakes actually protect their nests and newborns.

A: Despite observations dating back hundreds of years and peer-reviewed research published in the 1990s, most people believe that snakes are on their own, able to care for themselves, from the moment they’re born or the egg is laid. But many snakes actually protect their nests and newborns.

In rattlesnakes well-studied enough to know, families stay together until the babies have shed their skin for the first time – ~7-14 days after birth. And in the few species we’ve investigated, it doesn’t stop there. Timber rattlesnake (C. horridus) juveniles and adult females tend to associate more closely with their relatives at communal dens and rookeries (gestation/birthing sites)2. In our work with Arizona blacks, we’ve observed that many babies end up at their mother’s den (we’ve never observed one at a different den) and continue to associate the following spring.

Q. It’s amazing that some snakes will actually maintain “friendships”, whether with family members or unrelated snakes. What are some of the ways snake friends tend to interact?

That’s a very good question. We are just learning about social behavior in snakes outside of that related to reproduction (e.g., courtship, combat). For our research, we used proximity as our metric of association; if snakes were within a body length of each other (and thus could identify each other by scent and sight), we classified that as an association. While we did also record whether they were touching, we didn’t analyze at that scale (due to small sample size) or record any more specific behaviors.

Anecdotally, most snakes in association were observed resting together, sometimes basking in the sun. This video of Spooky and Ali was taken with one of our timelapse cameras above a communal basking spot and is a good example of social snake behavior. They were adult female Arizona black rattlesnakes that were observed together 57% of the time – one of the strongest bonds/friendships we observed. (See video below)

Q: You’ve observed3,4 mother rattlesnakes protecting and caring for their young. What are some of the ways in which they do this?

A: Newborn rattlesnakes are much smaller and less wary of threats than adults, so the simplest form of care mothers do is to be present (or watching nearby) when babies are on the surface. When the babies are very young (~1-3 days), mothers tend to keep them very close and will herd them back if they move away3. If the nest is threatened, the mother will employ the usual rattlesnake defenses: posturings, rattling4, and probably striking/biting if it escalates that far (not something I’ve personally tested 🙂 ). Greene and colleagues previously documented similar behavior in other rattlesnake species5. Like other animals, their behavior develops: babies become less naive and mothers less protective during that 1-2 week period.

What most people consider caring for young, i.e., feeding, rattlesnakes do not do (that anyone has observed). But, they may partition heat, which is a more important resource for newborn rattlesnakes. Because adults are larger they retain heat longer than babies with their high surface area to volume ratio. We often see babies piling on adults and this may be why, in addition to protection offered from predators.

Q: You’ve also found6 that rattlesnakes will help “babysit” the offspring of other rattlesnakes. What do the snakes do when looking after these other young?

A: Except for threatening potential predators, we have observed babysitters doing everything we’ve observed in mothers. Whether they don’t defend, or we haven’t observed it yet, we don’t know (haven’t tested it). Unless the babysitter is a male or still-pregnant female, genetic testing is required to determine if it’s babysitting, so this behavior has likely been observed more often than we think.

Q. Is it known whether or not the babysitter snakes are sometimes friends or relatives of the mothers? In either case, it seems to imply that snakes have some capacity for cooperation.

A: I WISH! Again, because we haven’t done the genetic analyses on our snake population, we don’t know if babysitters are relatives. The association data we analyzed were from the spring, as snakes emerged from their winter den. A question that emerged from our results was whether spring association patterns predicted summer association patterns (e.g., communal gestation, babysitting), but we haven’t done that work yet. (In a quick look at our data, I’m not seeing any helper/mother combinations in the list of snake friends.)

As is often the case when studying a topic not well explored in a taxa, our research gave us many more questions than answers. 🙂

Q: Can you tell us a bit about any other research projects you are currently conducting?

A: We continue to monitor the population of Arizona blacks where we studied social and parental behavior, though not as closely, and we’re still collecting genetic samples to see if relatedness explains any of the social bonds we quantified. But our main focus now is to use what we’ve observed to help snakes. Snakes are unjustly demonized, which has led to widespread persecution and often made their conservation difficult. We decided snakes needed advocates more than another couple scientists, so we formed a nonprofit to do that.

Q: What was one of your most incredible moments in the field?

A: The most exciting moments in the field for me have been seeing my old friends again. By mostly leaving them alone and getting to know their habits,we’ve been able to see the same animals year after year. We’ve observed a few females with their families 2-3 times (they only give birth every 2-3 years, but tend to use the same or nearby nest site), and are now seeing their kids tend families of their own.

A: The most exciting moments in the field for me have been seeing my old friends again. By mostly leaving them alone and getting to know their habits,we’ve been able to see the same animals year after year. We’ve observed a few females with their families 2-3 times (they only give birth every 2-3 years, but tend to use the same or nearby nest site), and are now seeing their kids tend families of their own.

Mr. Right was born in 2010, to one of the first rattlesnake families we monitored. We saw her again in Spring 2012 at a nearby den with one of her nestmates. This past August (2015) we found a very pregnant Mr. Right at a rookery very near her birthplace. It was so exciting to see one of our babies all grown up and know that she had survived to reproduce – as many likely do not.

Q: What fact about snake cognition or behavior do you think is most important for the world to know?

A: Snakes are more like us than people realize. They learn. They care for their kids. They care for their neighbors’ kids. In some cases, they have families and friends they visit throughout their lives. They have homes with favorite places to get food, meet friends and mates, rest, and shelter from predators and inclement weather. Humans tend to otherize people and animals we perceive as different and treat them poorly. I hope that by helping people see that snakes share many behaviors with us, behaviors we value, people will choose to treat them better, and cruelty like wanton persecution of snakes and rattlesnake roundups will no longer be socially acceptable.

This interview was conducted by Amanda Pachniewska, founder & editor of Animal Cognition.

Links

1 – Melissa Amarello, Jeffrey J. Smith

Social Snakes? The Role of Kin Selection in Rattlesnake Aggregations

Sonoran Herpetologist

http://www.snakes.ngo/Amarello_Smith_2012.pdf

2 – Rulon W. Clark, et al.

Cryptic Sociality in Rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) Detected by Kinship Analysis

Biology Letters

http://www.bio.sdsu.edu/pub/clark/Site/Publications_files/snake_kin.pdf

3 – Melissa Amarello

A Day in the Life of Rattlesnake Families

Advocates for Snake Preservation

http://www.snakes.ngo/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-rattlesnake-family/

4 – Melissa Amarello

Sigma vs. the Squirrel

Advocates for Snake Preservation

http://www.snakes.ngo/a-day-in-the-life-of-a-rattlesnake-family/

5 – Gordon W. Schuett, et al.

Biology of the Vipers

https://s3.amazonaws.com/eaglemountainpublishing/biology_of_the_vipers.html

6 – Melissa Amarello

A Rattlesnake Helper?

Advocates for Snake Preservation

http://www.snakes.ngo/a-rattlesnake-helper/